The many maps in Spielberg’s “Lincoln”

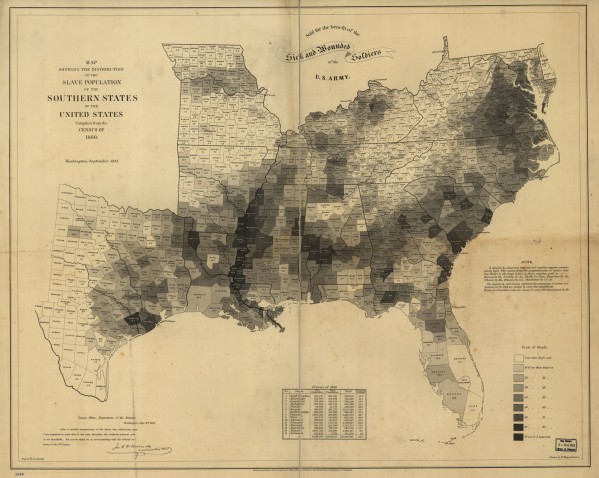

I just saw Steven Speilberg’s film “Lincoln,” and was amazed by the space given to maps on the set. The maps are never referenced directly, for the plot of the film is the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment in early 1865. But there are maps everywhere, first among them this map of slavery issued by the Coast Survey in September 1861.

Much of my knowledge of Coast Survey map making has been learned from John Cloud, historian at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Agency. John and I, together with census historian Margo Anderson, have puzzled over the role of the slave map, which became one of Lincoln’s favorites, and which I have written about extensively in the “Cartography of Slavery” (2010) and in chapter four of Mapping the Nation (where you can see a high-resolution image). I was thrilled to see this work incorporated into the movie; the film is based primarily on Doris Kearns Goodwin’s Team of Rivals, but she does not address the map or its complex relationship to the war.

In the film, the map is suspended on a roller in both the war department as well as the telegraph office. This is a bit of creative license: my evidence indicates that Lincoln viewed the map in its original (smaller) size, spread on a table rather than suspended from the wall.

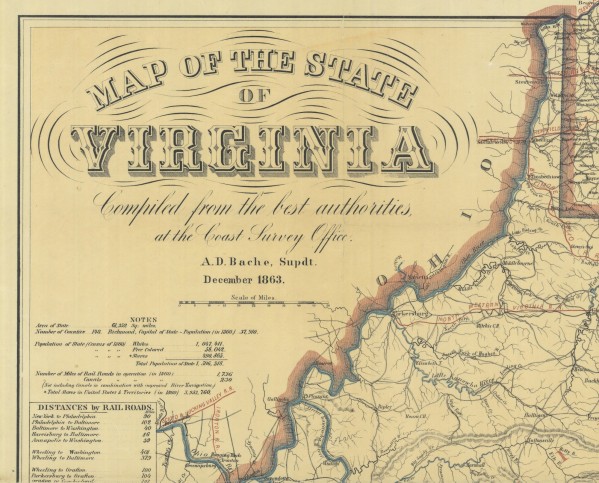

But the decision to hang the map on the set enriched the film (in my view, anyhow). It is seen alongside the stunning Map of the State of Virginia issued by Bache and the Coast Survey in 1863:

The film places Lincoln, Seward, and Thaddeus Stevens at the center of the intrigue surrounding the fight to pass the Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished slavery in the Constitution. There is too much political detail to capture here, but for me one irony stands above all the rest: in Lincoln’s First Inaugural Address, a very different Thirteenth Amendment was proposed, one that would protect slavery from any federal interference. Lincoln extended the offer to the southern states in March 1861 as a way to reverse or slow the momentum around secession. Southerners were unmoved, of course, and rejected Lincoln’s offer. The war resulted, which made it possible for Lincoln and Congress to destroy the very thing that slaveholders sought to protect through secession.

I also spotted the Coast Survey’s map of Charleston Harbor — I think it is this one. Tell me if you noticed others!

- Click to open in new window.

Use controls to zoom and pan.

[…] Next up, Susan Schulten writes about the maps used in “Lincoln.” […]

I believe this map, or one very like it (complete with positions of ships), was used in the early part of the film, when Stanton was briefing the Cabinet on the assault on Fort Fisher. They kept talking about the assault being on Wilmington,” which is not really right, but otherwise they would have had to go ibto a lot of expository dialogue about NC coastal geography, and why taking Fort Fisher would close the port of Wilmington, etc., etc.

Hi Andy: Thanks for this! I had never come across that map, and am impressed by its detail. For those interested, here is the version included in the Atlas to Accompany the Official Records.

Of course, that map was prepared after the fact, to show how the bombardment was actually carried out, as opposed to the plan for the bombardment, but still — not as bad as the scene in Gods and Generals, where the Confederates are discussing strategy over maps reproduced from the OR Atlas. 😉

Thanks Andy!

I haven’t seen Gods and Generals, but that’s a pretty good anachronism!

I’ve often thought the production of the OR Atlas would be a great subject for research — particularly the process of transforming the maps into “official” records several decades after the fact. One that particularly struck me was Wool’s map of the Peninsula in early 1862, which was reproduced both in its erroneous and corrected form in the OR atlas.

And given that Julius Bien did much of the lithography, at the height of his power and popularity, I think there’s got to be a good story about how the Atlas came about.