Why Republicans mapped slavery in the 1856 election

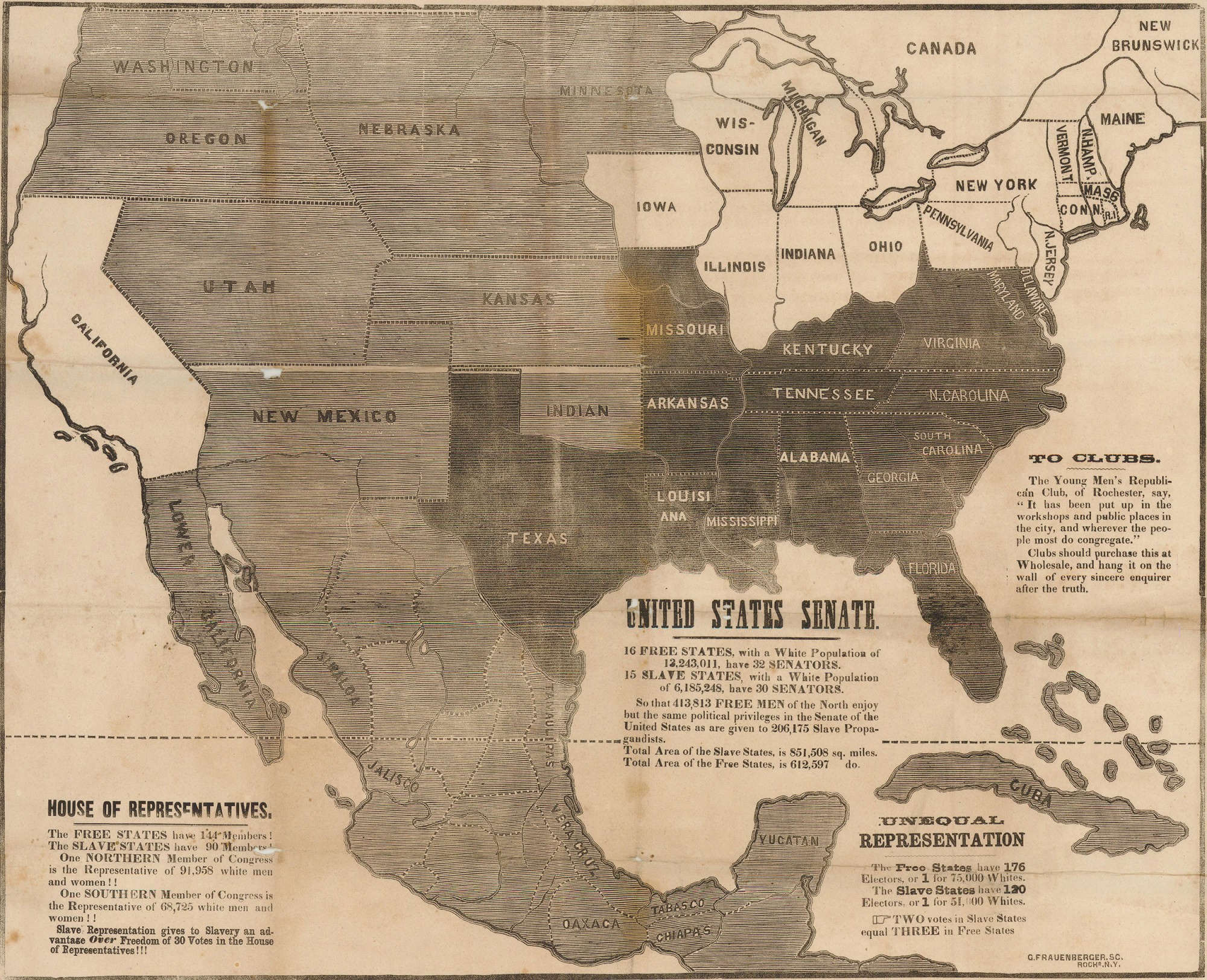

Jon Dotson, owner of Old World Auctions, recently showed me a political broadside from the 1856 campaign, when the new Republican Party ran its first presidential candidate, the celebrated western explorer John C. Fremont.

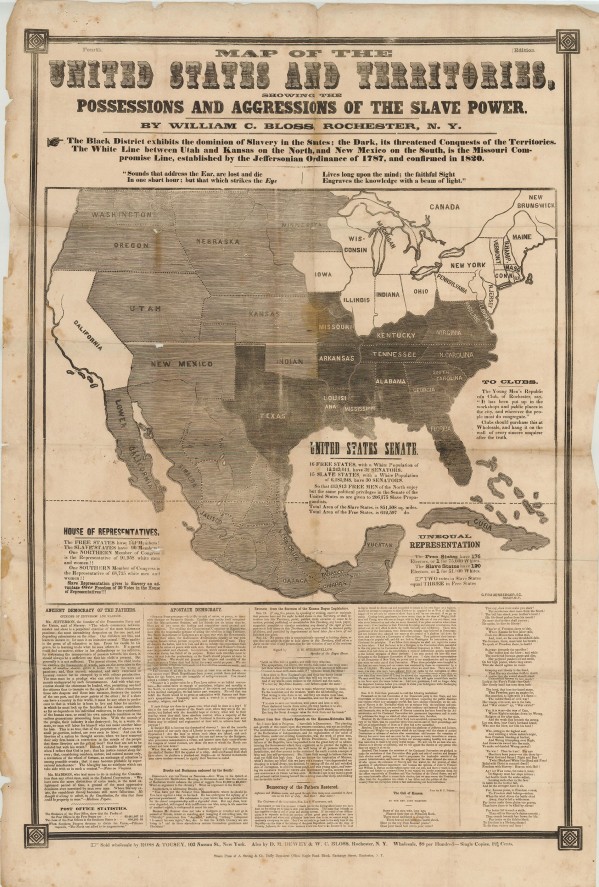

This rare broadside is just one of many that party supporters made to fight both the extension of slavery and the Democratic candidacy of James Buchanan. It was was designed by William Bloss, an anti-slavery activist in Rochester hoping to draw voters to the Republican cause. That it is a “fourth edition” gives us some sense of the chord it struck among anti-slavery New Yorkers.

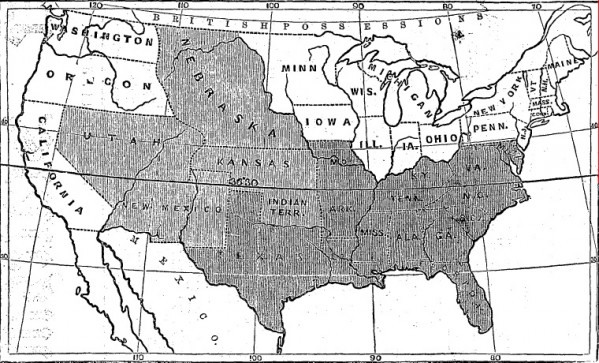

Republicans used maps extensively to advance their cause in the 1850s. In January of 1854, Stephen Douglas introduced a bill to transform what had been “permanent” Indian country into two new territories of Kansas and Nebraska. Douglas added a proviso allowing the future residents to determine the existence of slavery in the region, which overturned the longstanding geographical separation between slave and free territory mandated by the Missouri Compromise of 1820 along the line of 36 30 that is marked on the map.

Douglas introduced the bill for several reasons, but mostly to cultivate the support of southern Democrats who worried that the future of slavery—and of slave state representation—was blocked by the Missouri Compromise. But his decision to repeal the Compromise outraged northerners in a way that can hardly be overestimated. They defected from the Democrats and Whigs to form what eventually became the Republican Party, dedicated to halting the extension of slavery.

Below is one of the first of those maps from a newspaper in early 1854, at precisely the time the Republican Party was taking shape. Its crude and direct manner conveys the urgent fear that Douglas had opened the door to a nation dominated by slavery.

Two years later, the Republicans used maps extensively in the presidential campaign of 1856. The opening of Kansas had turned bloody very quickly, and was on everyone’s mind. Those fears of slavery moving west were confirmed by the 1857 decision in Dred Scott v. Sanford, which determined that Congress had no right to forbid slavery in the territories.

The broadside and map is a window not just onto the campaign of 1856, but also onto an era when Abraham Lincoln was converted to the Republican cause. It was the Nebraska Bill, after all, which convinced him that Douglas’ vision of the nation was fundamentally flawed, and that the framers had intended for slavery to die a natural death. Lincoln spent the next several years articulating this vision, which culminated first in his confrontation against Douglas in their famous debates, and then in his victory in the 1860 election.

These maps here make a powerful political argument through a single powerful image. As Bloss himself noted, “that which strikes the eye lives long upon the mind.” In chapter four of Mapping the Nation, I discuss several more of these maps of slavery. Above all, they convey the northern fear that by 1856 the nation was fatally divided not along partisan lines, but sectional ones. Maps were uniquely capable of capturing that hard political truth.

Special thanks to Jon Dotson at Old World Auctions for generously sharing the Bloss broadside with me.

Use controls to zoom and pan.

[…] Here, for instance, is another one with the same urgent call to mobilize against slavery. It measured about 2 feet wide by 3 feet, designed to be hung publicly. No matter what their size, each iteration of this anti-slavery campaign map uses the same data–expenditures on the mails, congressional representation–to show a nation that is controlled by slaveholders. […]