How Sherman’s march helped Lincoln win in 1864

We’ve just survived another election season, with the attendant (and often hyperbolic) claims that the nation’s future hinges on the outcome. In the aftermath, it seems fitting to recall another campaign—exactly 150 years ago—that really did influence the fate of the republic.

In the fall of 1864, President Lincoln faced a series of obstacles in his bid for reelection. The civil war had dragged on for over three years, and the inability of the Union Army to capture Richmond and control Virginia led many Americans to doubt that victory was in sight. Lincoln himself faced criticism on all sides: many anti-war Democrats insisted he was a tyrant who cavalierly imposed a draft and violated civil liberties, while his fellow Republicans charged that he was insufficiently prosecuting the war against the Confederacy. The big gains of 1863—Gettysburg and Vicksburg—began to seem like distant memories. The party even flirted with the idea of dumping Lincoln for another candidate, and a pesky third-party candidate, John Fremont, threatened to steal away the votes of unsatisfied Republicans.

That grim summer, Lincoln actually acknowledged that he might lose the election. Such a prospect was particularly terrifying to Lincoln, for a repudiation of his administration was a repudiation of the war itself. The Democrats were about to adopt a platform that promised immediate negotiations to end the war with the Confederacy, which would have meant an end as well to his efforts to permanently end slavery with a Constitutional effort. Adding insult to injury, the opposing party nominated Lincoln’s adversary, General George McClellan, whom Lincoln had fired two years before. Reelection was essential; losing meant losing the war. What Lincoln needed, above all, was tangible evidence that the Union was on its way to victory over the South.

The Democrats put McClellan forward on August 31. His nomination enjoyed the spotlight for a single day before it was eclipsed by stunning news from the front: on September 1, Confederate forces had surrendered Atlanta to Union forces under the command of General William Tecumseh Sherman.

The timing shows the intricate relationship between the battlefront and the home front. Sherman’s victory gave the embattled president hope. Though this was not the only factor in the election, it certainly demonstrated strong territorial gains for the Union. And Lincoln won big on November 8, crushing McClellan with a 212-12 win in the Electoral College and 55 percent of the popular vote. Had McClellan won, General Sherman’s march through Georgia would surely have come to an end. But instead, just days after the election, Sherman took his men on one of the ambitious and risky campaigns of the war, cutting loose from his supply line to cut a sixty-mile swath through to the sea. He reached Savannah on December 10, presenting the city to the president as an early Christmas gift.

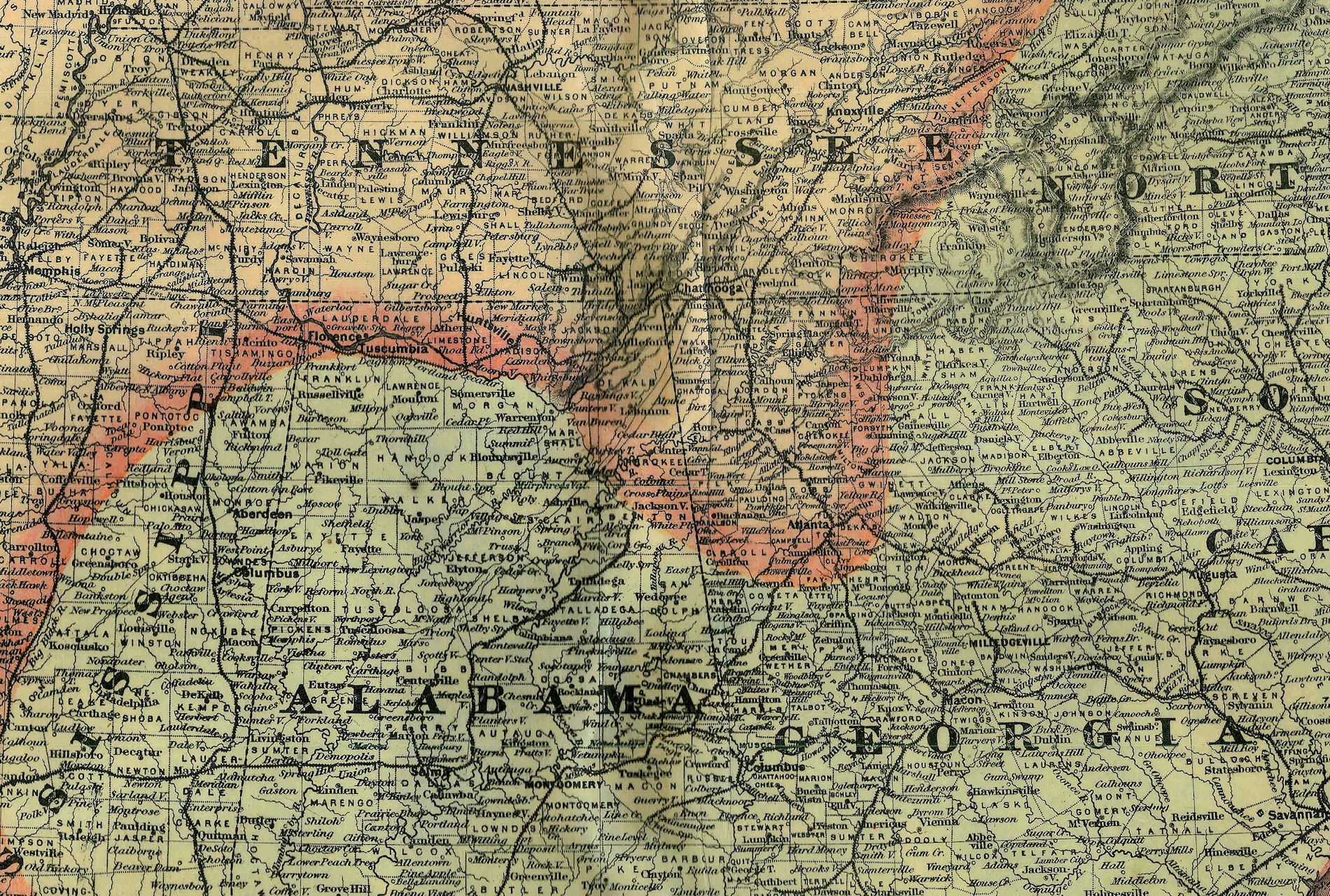

It was at this moment, just after the election, that Lincoln’s top engineers delivered a series of maps to the Senate to demonstrate the substantial victories made by Sherman and the larger hope that victory was near. A few illustrated the particular victories, reflecting the Corps’ traditional responsibilities of mapping forts, harbors, and specific theaters of war. But the most powerful maps were those that completely departed from this role: two national maps that dramatically contrasted the extent of Union territorial control at the outset of the war and the current moment.

To demonstrate these gains the Chief Engineer of the Corps took a commercially published map of the U.S. and colored those areas under Union and rebel control in 1861 and 1864. Notice that in the 1861 map even the formally loyal slave states of Missouri and Kentucky are partially colored in rebel color, as if to acknowledge the very real Confederate sentiment in those states.

This made the contrast to the second map representing November 1864 all the more apparent and tangible. If Virginia remained stubbornly Confederate, there were still huge and undeniable territorial victories. The Navy blockade now secured much of the Confederate coastline. The conquest of the Mississippi had completely bisected the Confederacy. But it was the gains in Georgia that prompted the Corps to make the map, for they showed an incursion into the heart of the Confederacy, and correspondingly signaled the war’s final phase. The map indicated progress through clear lines, which of course belied the terrible turmoil and chaos on the ground.

Sherman’s conquest is remembered as one of the most controversial campaigns of the war. But the outcome mattered not just for the war but for politics. The dual victories on the battlefield and at the ballot box gave Lincoln the mandate not just to continue the war, but to press the House to pass a constitutional amendment permanently ending slavery in the US.The convergence of these two campaigns—one political and the other military—left a permanent legacy.

[NB: As I explain in chapter two of Mapping the Nation, this innovation of representing the progress of the Union Army with a single line dates back to 1862, when the Coast Survey created a series of maps to illustrate the shifting tides of the war.]

Images courtesy of the National Archives. With thanks to the New Republic for permission to repost.

Use controls to zoom and pan.