An alternative map of the American west

Could the map of the west have been drawn in a fundamentally different way?

Last month I was interviewed by BackStory with the American History Guys for a show on the role maps have played in history. The story included a segment with Don Worster, an eminent professor of western and environmental history at the University of Kansas.

Worster described a beautiful–and extremely controversial–map made by John Wesley Powell, the intrepid explorer and leading natural scientist of the late nineteenth century. Powell is best known for his insistence the west must be understood as an arid region, one that demanded irrigation and management rather than a reliance on rainfall. In the late 1880s, Powell undertook a large-scale survey of the far west to demonstrate that the region was made up of interdependent watersheds, or what he termed irrigation districts. With his team, he measured the flow of water across one billion (that’s right!) acres of land in order to determine the shape of the landscape’s most precious resource.

In 1890, Powell was called to testify before Congress about his plan to halt the rapid distribution of land through the Homestead Act, and instead to think more systematically about creating communities organized around the efficient use of water for the benefit of the most. He freely acknowledged his debt in this idea to Mormon colonies and the Mexican acequia system of community management.

To drive home his point to Congress, Powell relied on several maps, including one of forests (the technique of mapping forests was itself new). But perhaps his most striking evidence was this beautifully colored patchwork map of western watersheds.

But for all his conviction and evidence, Powell failed to convince enough members of the committee. While a minority report endorsed his vision of an alternative blueprint for settlement of an arid west, the majority rejected his recommendations and continued to distribute land for farming in the way that they had for decades. Worster’s biography of Powell is incredibly informative and well-written, and details not just this but all of Powell’s expeditions in the west.

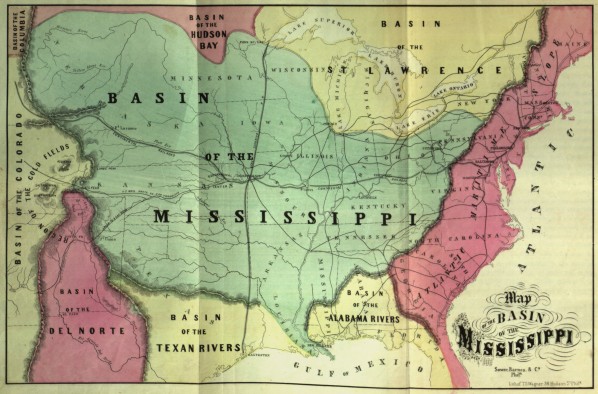

Powell was building on a long tradition of mapping not according to topography or political borders, but hydrography and watersheds. One of the most dramatic of these early hydrographic maps was created by William Gilpin, the avid western booster and first governor of Colorado Territory. From the 1840s to the 1870s, Gilpin relentlessly promoted the interior west–especially the Rockies and the High Plains–as the future heart of America, not just geographically but economically. He also used maps (to a very different end from Powell, surely) to advance a certain view of American geography.

Gilpin’s 1860 map stretches the limits of the imagination, claiming much of the country for the interior. But like Powell’s map, it was designed to show the “real” contours of the landscape, which demanded a logic entirely separate from the survey and the grid.

Use controls to zoom and pan.

[…] in the 1800s, the Director of the U.S. Geological Survey proposed that we divvy up western states based on watersheds. There’s sound logic there. Much of […]

Do you know where can I buy a copy of Powell’s watershed map of the west?

Hello Monica: I don’t, but I do have a high resolution copy of it from the original report. If you send me a private email I can get it to you. Thanks! Susan