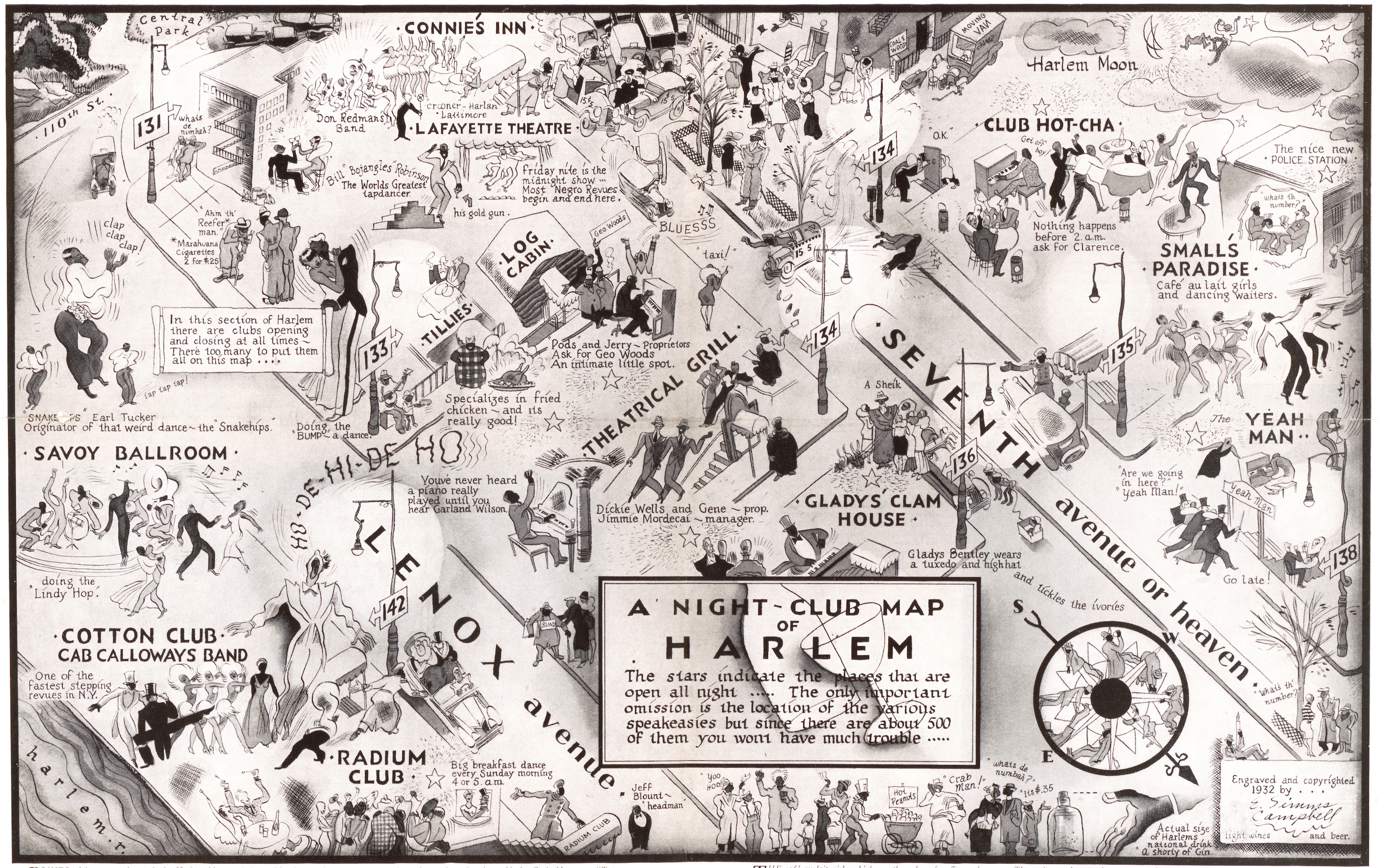

Mapping Magic–and Mayhem–in Jazz Age Harlem

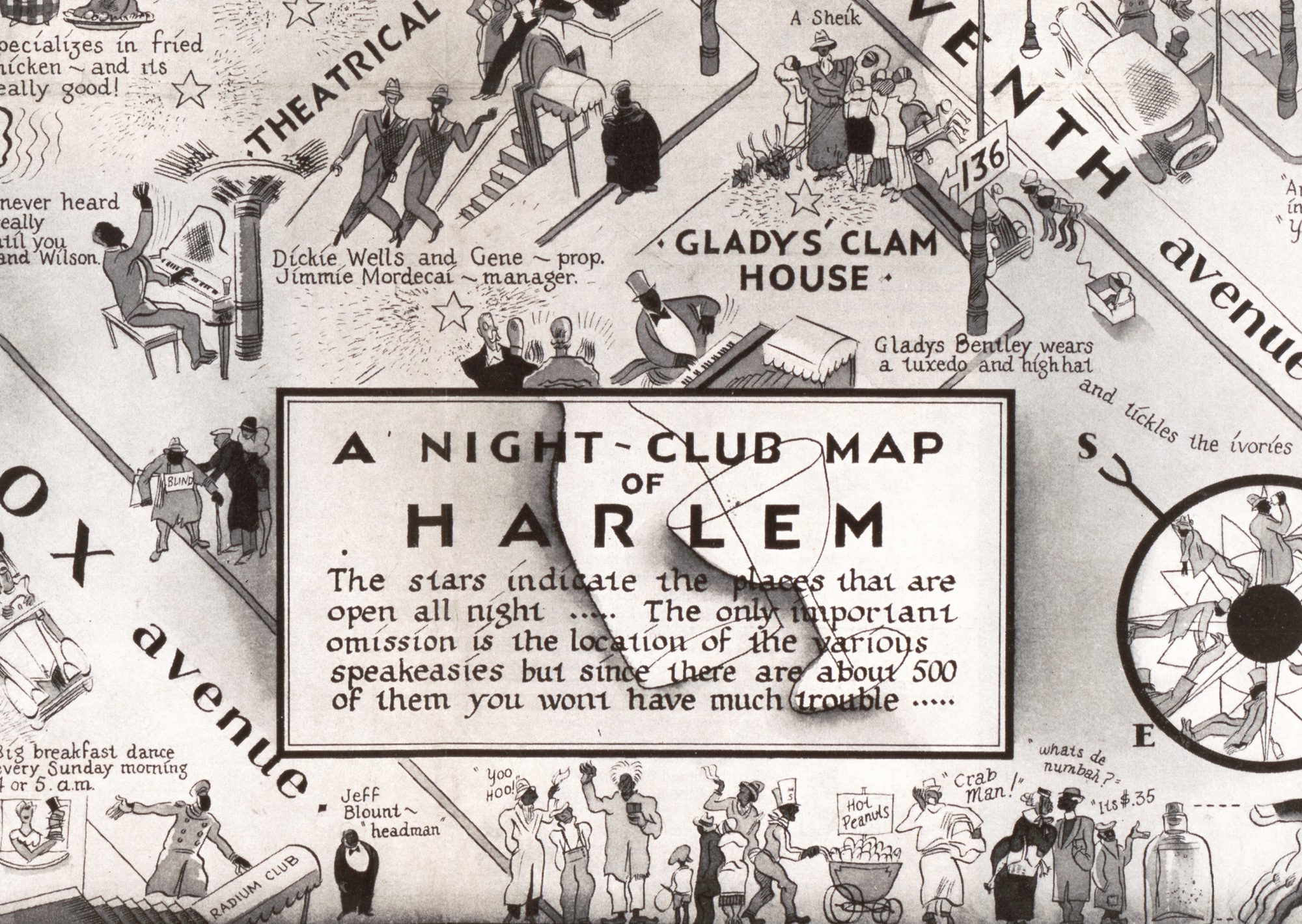

In 2016, the Beinecke Library at Yale University paid $100,000 to add Elmer Simms Campbell’s energetic profile of interwar Harlem to its celebrated collection of black history and culture. The Library described Campbell’s image as a “playful rendering” of the age, but it also captures the complex dynamics that made Harlem the cultural capital of black America.

Elmer Simms Campbell’s 1932 map of Harlem still captures the imagination of readers today. Click to open in new window.

This astronomical price for the map may even have surprised even Campbell himself. After studying at the Art Institute of Chicago, he moved to Manhattan in 1929 to seek work, though faced a string of rejections due to his race before catching a break at the newly founded Esquire magazine in 1933. For the next four decades, Campbell supplied the magazine with cartoons and illustrations that shaped its knowing, urban, and often cheeky sensibility.

Though he initially struggled to find work, Campbell immediately found a home in the Harlem’s jazz scene. He quickly befriended Cab Calloway, who along with Duke Ellington presided over legendary performances at the Cotton Club. The men became drinking buddies and regulars at Harlem’s famed clubs and speakeasies, all of which is immortalized in this loving tribute and gentle spoof. Campbell’s 1932 pictorial map of that moment thrilled Calloway so much that he kept a copy in his office.

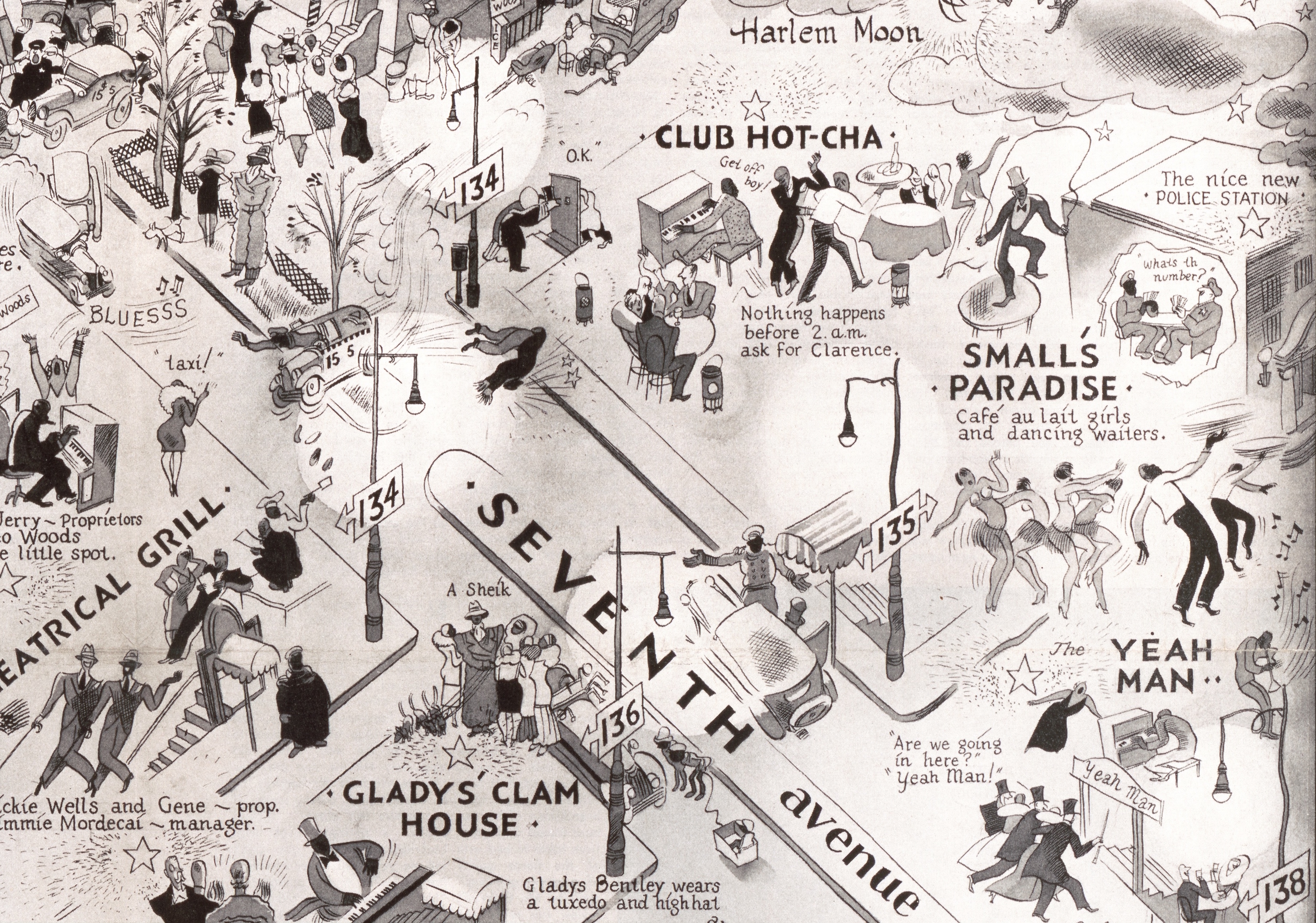

Above all, Harlem’s status as the “cultural capital of black America” resulted from the Great Migration of African Americans to northern (and increasingly segregated) cities in the early twentieth century. Even within Harlem, of course, while African Americans regularly performed at places like the Cotton Club, the clubs themselves remained segregated. Small’s Paradise was among the few spots both owned by and catering to African Americans.

Moreover, all of this exuberant nightlife was fueled by twelve years of Prohibition. And while it lowered the consumption of alcohol, Prohibition also fostered an illegal market that led to crime. Campbell slyly captures this pandemonium on the map, as whites made their way north to Harlem in search of urban thrills. Residents had little say in the permissive behavior that came to characterize their neighborhood: at left “marihuana” is sold openly, while public drunkenness seems almost a matter of course. Presiding over all of this mild mayhem in the upper right corner is a pair of officers enjoying the comfort of the new police station, wholly aware of the lawlessness outside.

The map was first published in early 1933, and by the end of the year Prohibition was over. Yet this twelve-year experiment vastly expanded the power of the federal government. As Lisa McGirr argues in The War on Alcohol: Prohibition and the Rise of the American State (2015), the Eighteenth Amendment created lasting enforcement practices and a vast penal state that had disproportionate consequences for African Americans throughout the twentieth century. In this respect, Campbell’s “playful” map inadvertently records much deeper cross currents of race, power, and culture in interwar America.

See more of the past through maps at www.america100maps.com.

Use controls to zoom and pan.