Schoolgirl maps from the early republic

I’ve been preoccupied lately with student manuscript maps, generally made by girls between 11 and 18 attending one of the many female academies of the American northeast between 1800 and 1830. “Map study” — as it was often termed — was a way for the girls to learn not just geography, but also to practice penmanship, drawing, and to improve their memory. What’s particularly interesting is that this was never part of a prescribed curriculum handed down to the individual schools, but a practice that spread when the students themselves became teachers at other schools. I’ve found hundreds of maps, most of which were drawn in the many schools that spread through the Connecticut River Valley, from Connecticut and Massachusetts up into Vermont and New Hampshire by the 1810s and 1820s.

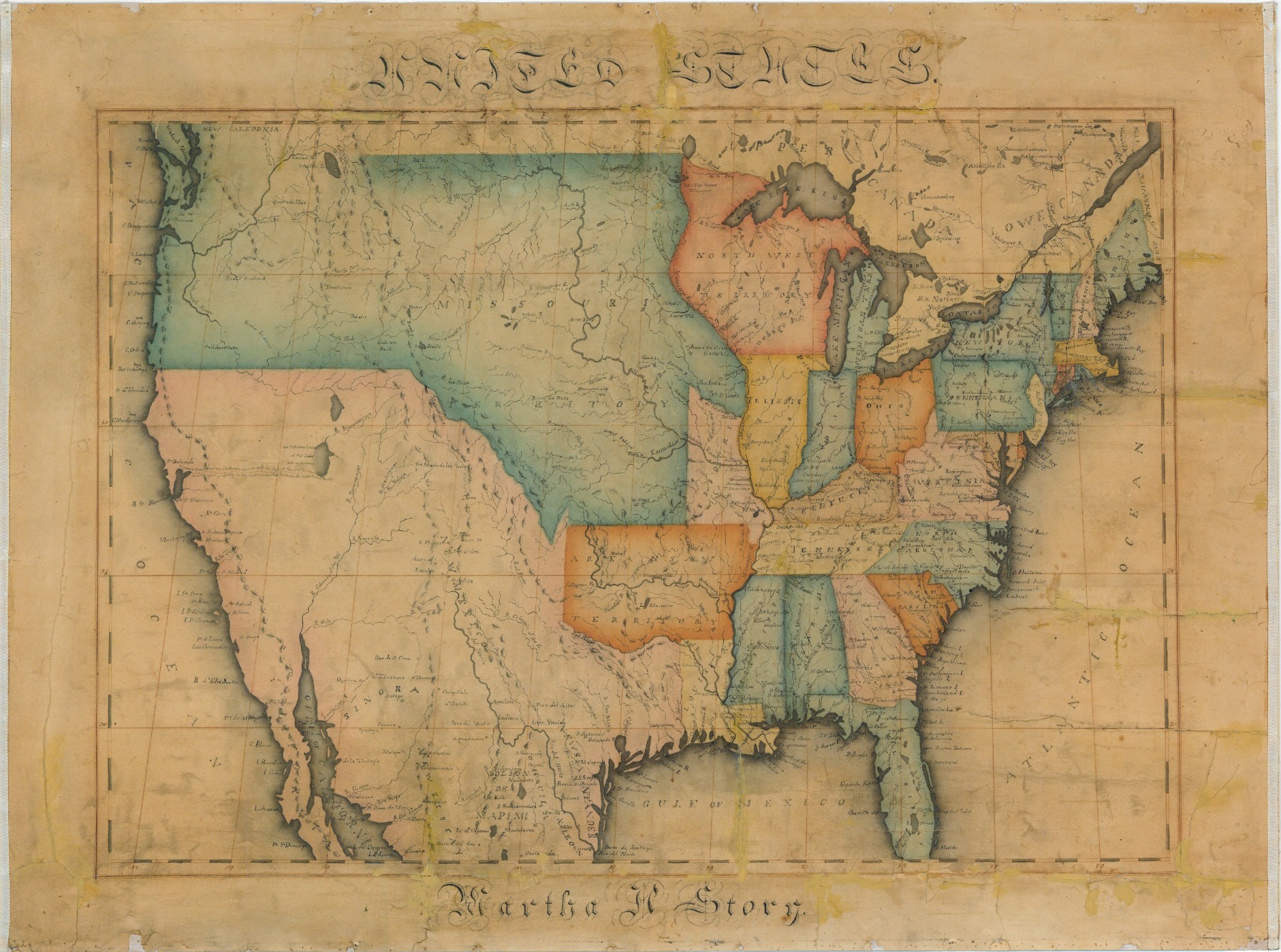

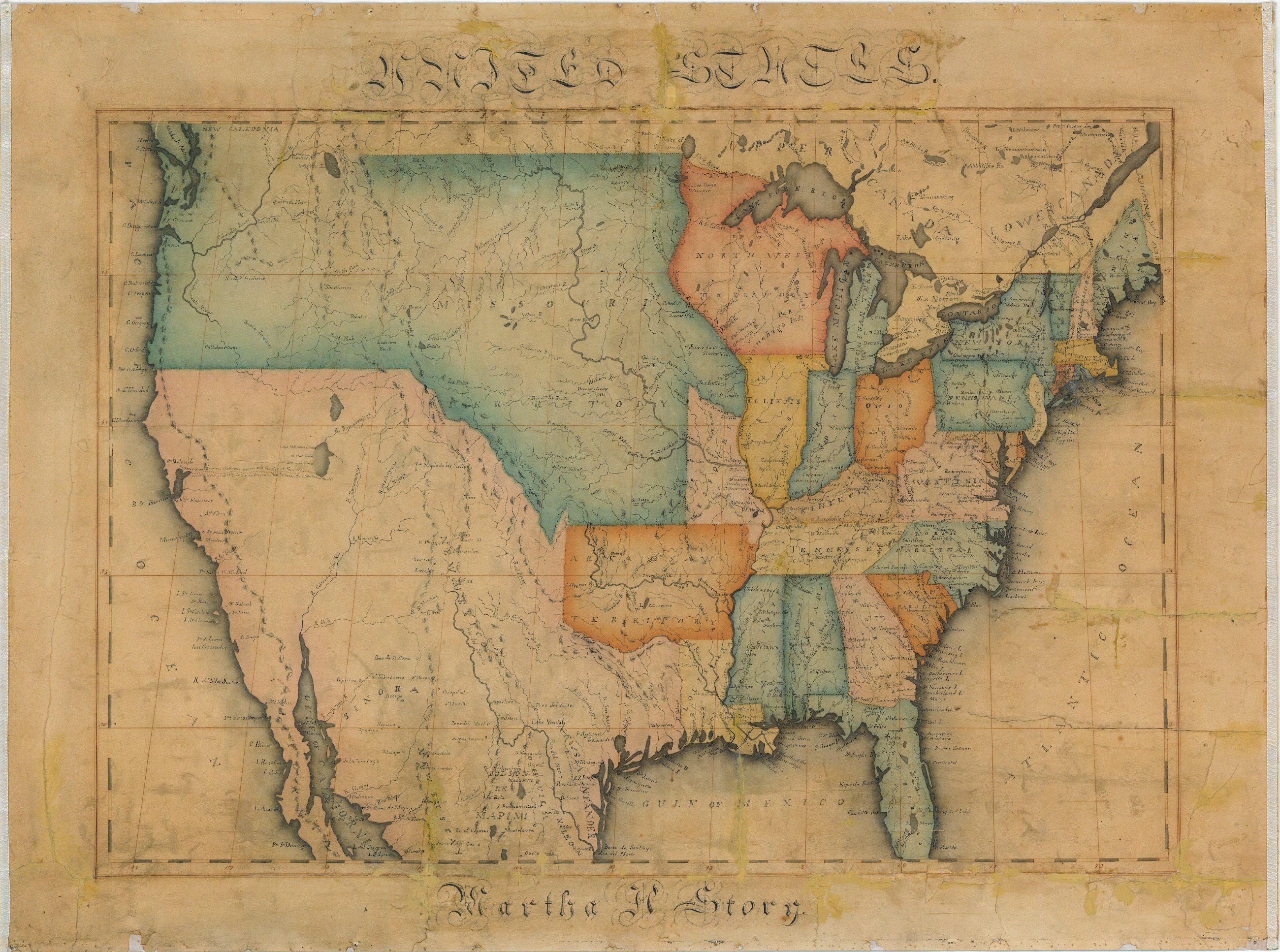

Here is a typical example found in the MacLean Collection, without a date but probably from the mid-1820s.

There is so much to be explored about these, and the more I study the more I learn. But here I just want to highlight a few observations. First, it seems that the maps were most commonly drawn in the 1810s and 1820s, when the female academy movement was at its height. Thereafter young girls had far more opportunities for study than map study, and hence far fewer maps.

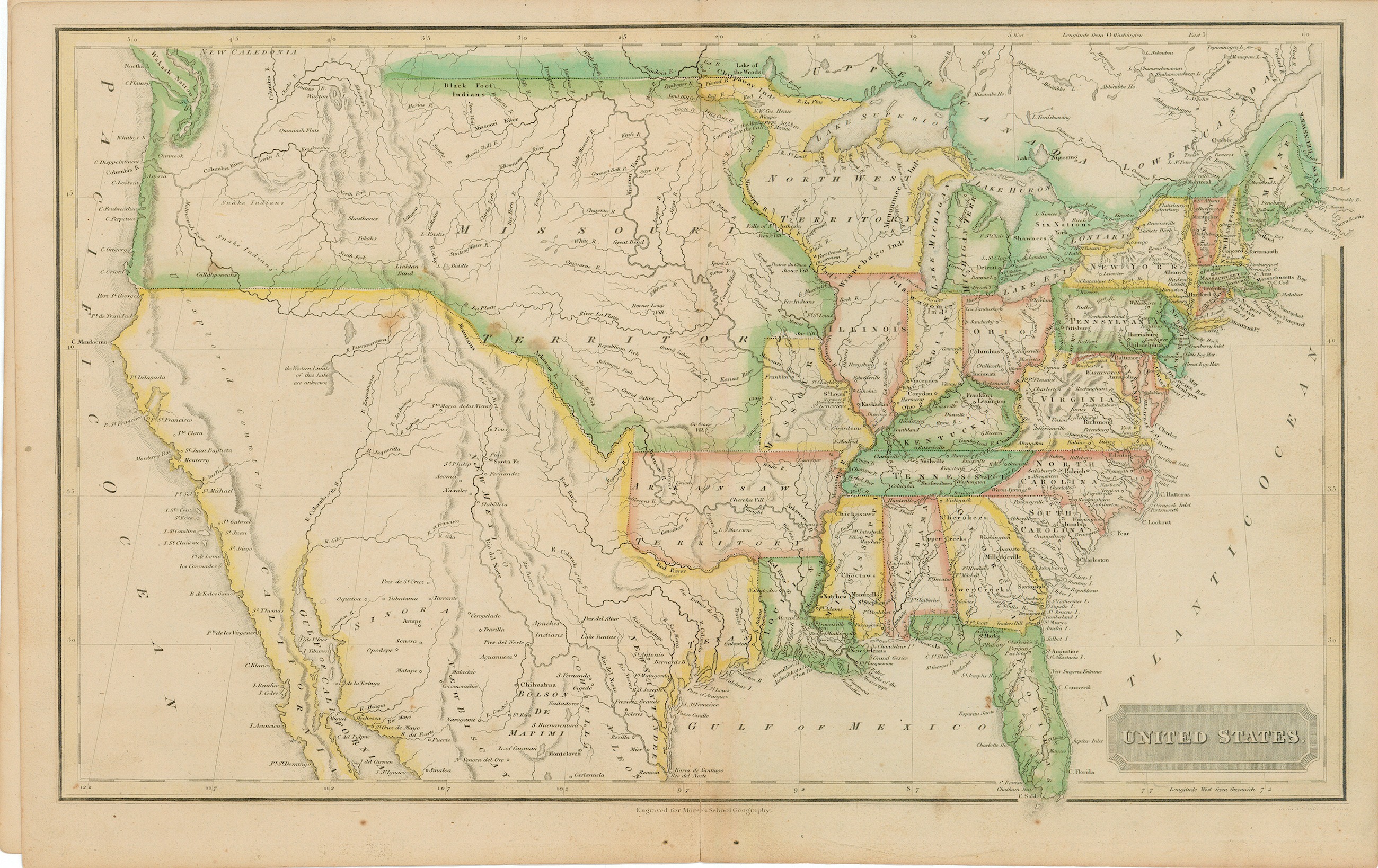

Second, mostly what we find in the archives are maps that were copied or adapted from published works. Martha Story was no doubt working from one of the earliest school atlases in the US, published by Sidney Edwards Morse.

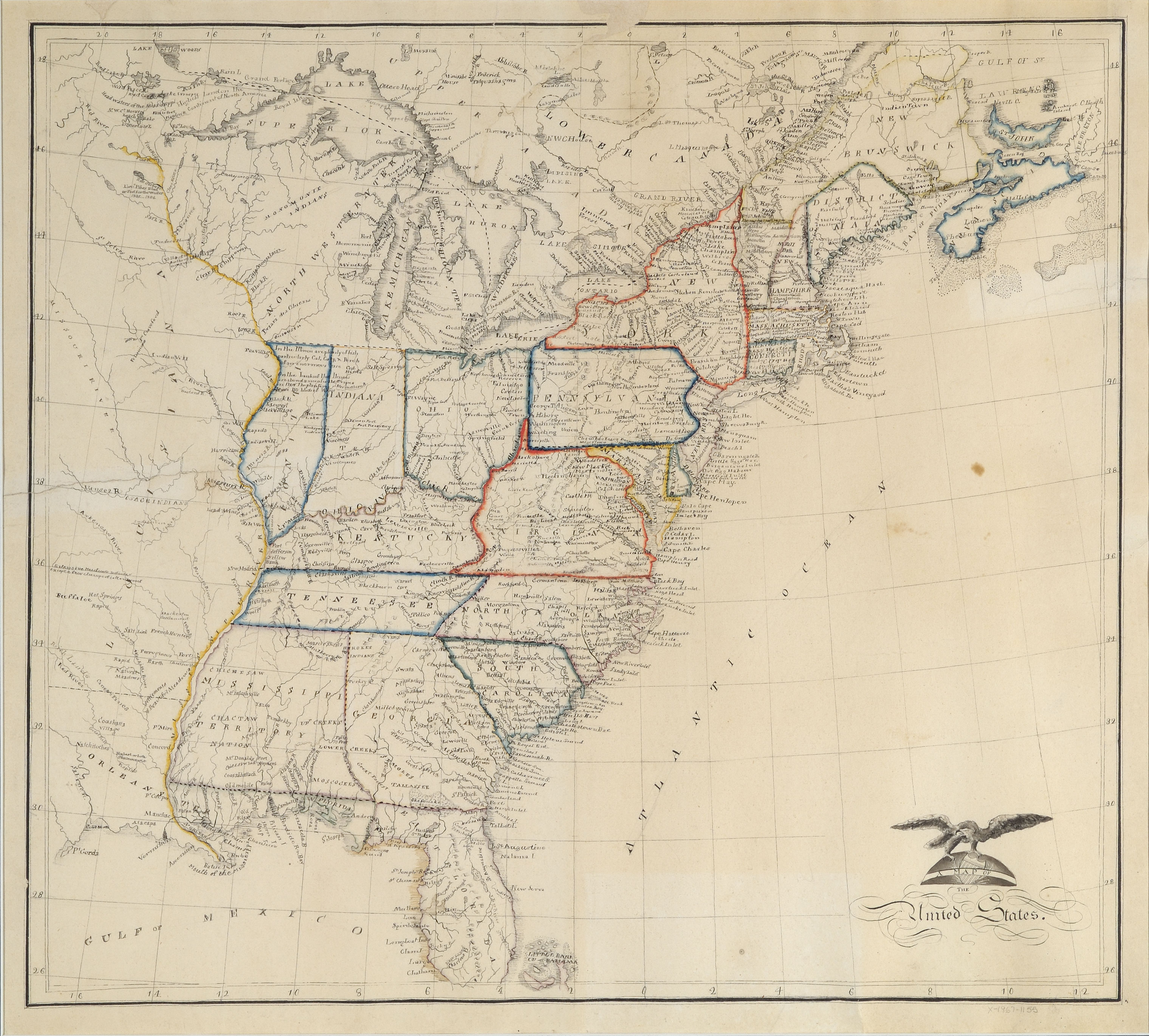

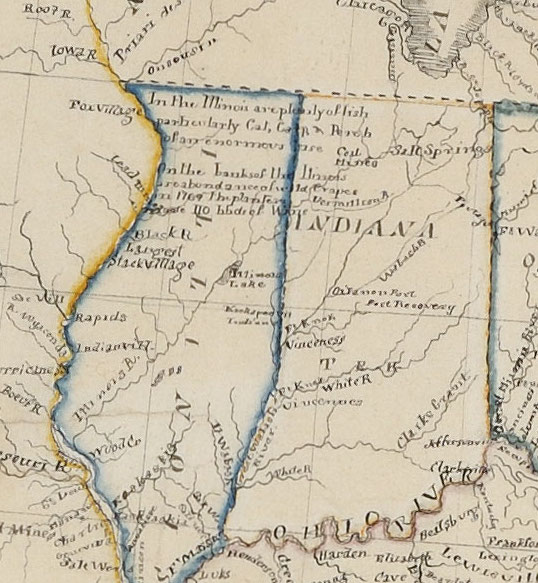

Sometimes the fidelity between the published and the children’s maps is so close that one wonders what students were being asked to do. With so little freedom to experiment, it seems they were practicing precision, calligraphy and lettering, coloring and attention to detail, but probably not “mapmaking.” Consider Caroline Chester, a sixteen-year old girl at the Litchfield Female Academy in the summer of 1816, who faithfully rendered the United States from Shelton and Kensett’s map, published during the War of 1812. Her map comes to us courtesy of the Litchfield Ledger.

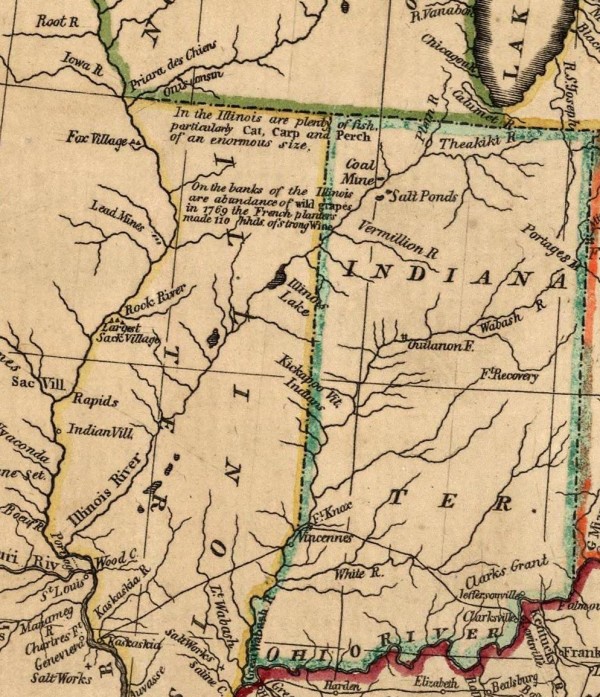

Even down to the notations on the maps and the cartouche, she has almost obsessively followed the published original (from the David Rumsey Collection).

Here for example take a look at Shelton and Kensett’s notations from the western territories, faithfully rendered in the second detail by Caroline Chester.

Finally, it is worth noting that the practice of map study was extremely common in these academies, yet no prescribed text or curriculum template existed. Instead, these practices spread as students themselves became teachers. I have found an extensive network of young women who brought these practices with them as they migrated through different schools. So far, most of the connections I’ve dug up are in the northeast, particularly along the Connecticut River Valley, but surely more are waiting to be found. As certain styles of needlework spread through schools and regions, so too did certain approaches to the study and reproduction of maps.

Thanks to David Rumsey, the Litchfield Historical Society, and the Maclean Collection for sharing these beautiful maps. I’ve just begun to explore what they might reveal about the history of education, the world of the female academies, and nineteenth-century visual culture.

Use controls to zoom and pan.

[…] and without doubt drawn by a child’s hand, quite likely a girl, as a study aid. Called ‘map study‘, scrutinizing and reproducing an atlas map afforded young girls the opportunity to learn […]

[…] of young men and women in the early republic. For the last several years I’ve spent time tracing some of these artifacts, and using them to reimagine the dense networks of teachers and students who used map drawing as a […]